The Importance of the Thoracic Sling

The goal of riding should be to have as healthy a sling as possible and have the horse use his sling as much as possible.

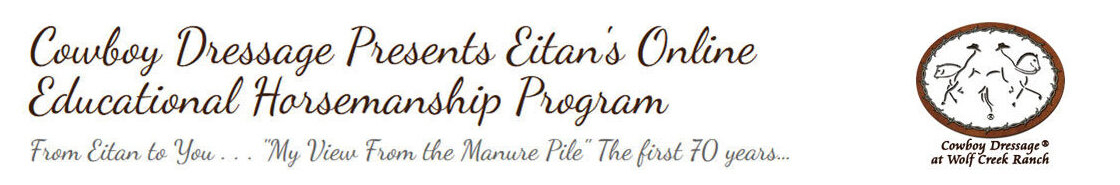

Riders may often focus on the hind end pushing through the back’ or more often the position of the head. Learning to feel when the sling is engaged could prove more useful and help the horse carry you whilst strengthening the necessary muscles. (fig-1)

(fig-1)-1.- Top line lengthens, poll goes forward. 2. -Withers Lift. 3.- Weight shifts to rear.

4.- Raising the base of the neck. 5.- Abdominal muscles engaged. 6.- Hind quarters engaged.

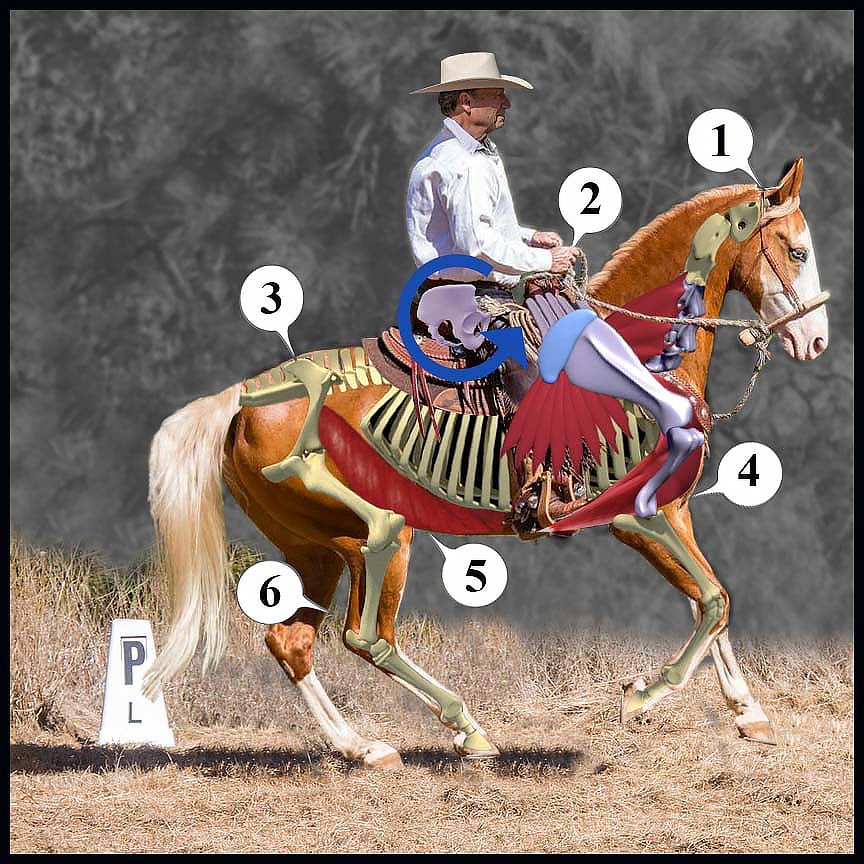

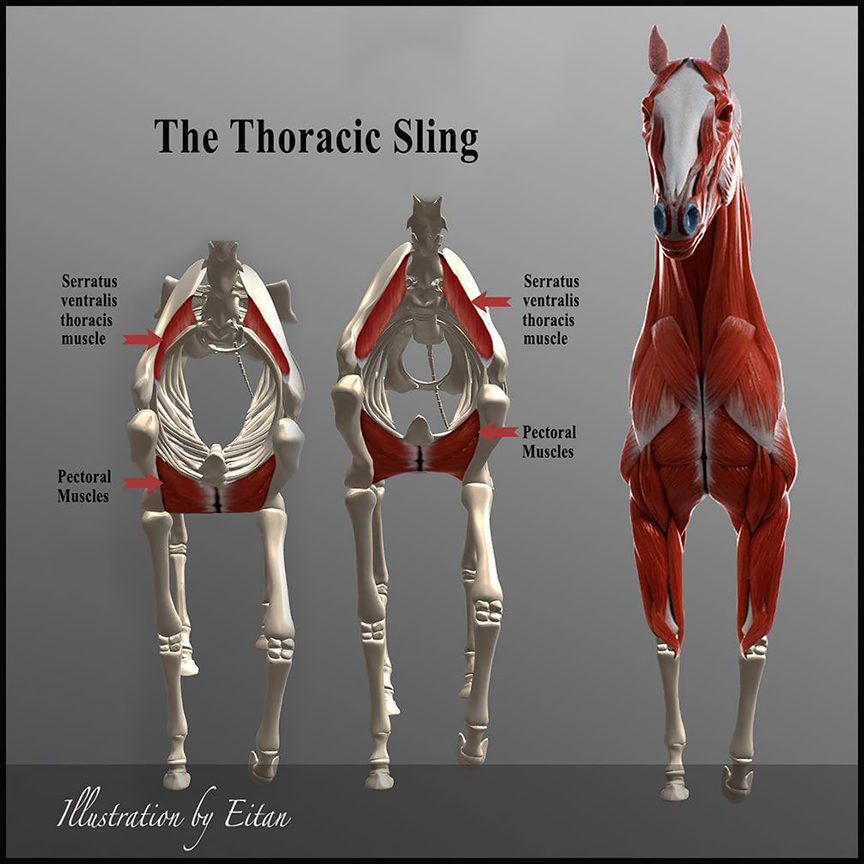

Unlike the human shoulder girdle where the collarbones (clavicles) attach the arms to the body, a horse has none. Without a collarbone, a horse has no bony connection between its front limbs and trunk. Instead, strong muscles connect the inside of its shoulder blades to its rib cage, which act like slings and suspend the chest between the horse’s two front limbs. The ‘sling muscles’ consist primarily of the serratus ventralis thoracis muscle assisted by the pectoral muscles. (fig-2)

The ‘sling muscles’ consist primarily of the serratus ventralis thoracis muscle assisted by the pectoral muscles. (fig-2)

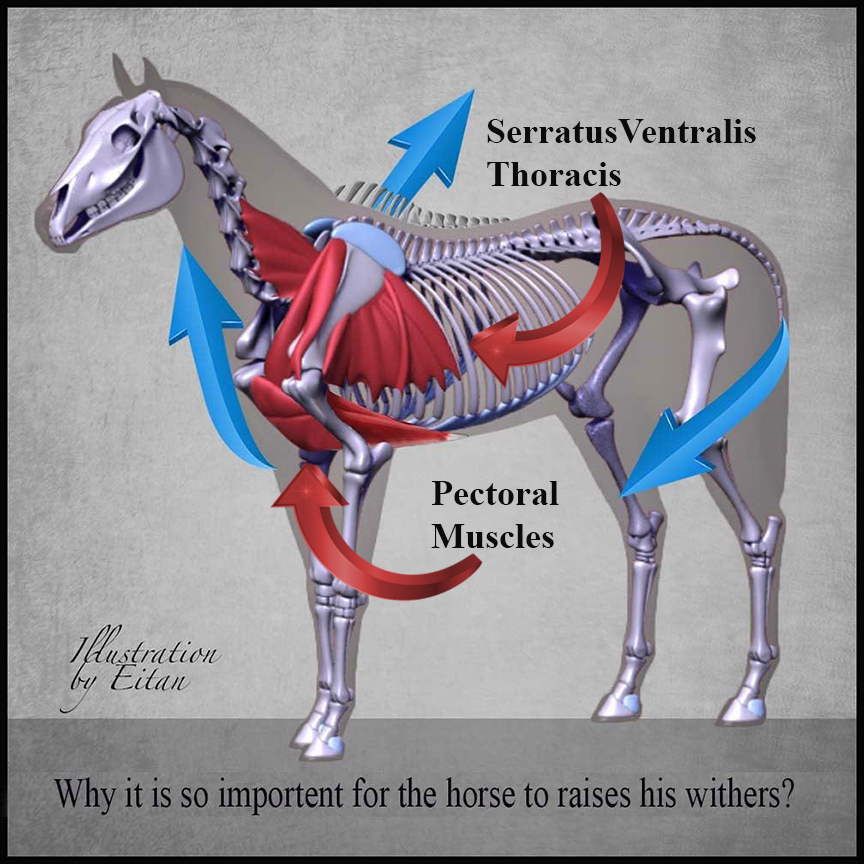

Contraction of these sling muscles lift the trunk and withers between the shoulder blades, raising the withers to the same height or higher than the croup. When a horse travels without proper contraction of its sling muscles, the horse’s motion looks downhill and on the forehand.(fig-3)

Contraction of these sling muscles lift the trunk and withers between the shoulder blades, raising the withers to the same height or higher than the croup.

The average horse carries more weight on its front legs then on its hind legs. The horse must learn to move in an uphill balance by pushing upwards with its forelimbs. The hind legs can then function as they should by carry more weight and by providing pushing power. The heavy chest needs to be up and out of the way for the hind legs to push. (fig-4)

The sling muscles are extremely important to the self-carriage of the Cowboy Dressage horse. The goal in training is to teach the horse to use its sling muscles throughout the workout. With time, these muscles get stronger and the persistent elevation allows the horse to push and hold its hind legs under the center of gravity through its motion to be even more uphill.

The work of the sling muscles increases with a rider who balances the shoulders throughout his or her training.

This raising of the frame, if balanced correctly by the rider, will allow those muscles to become stronger and more elastic and aid in the horse learning to hold its own frame.(fig-5)

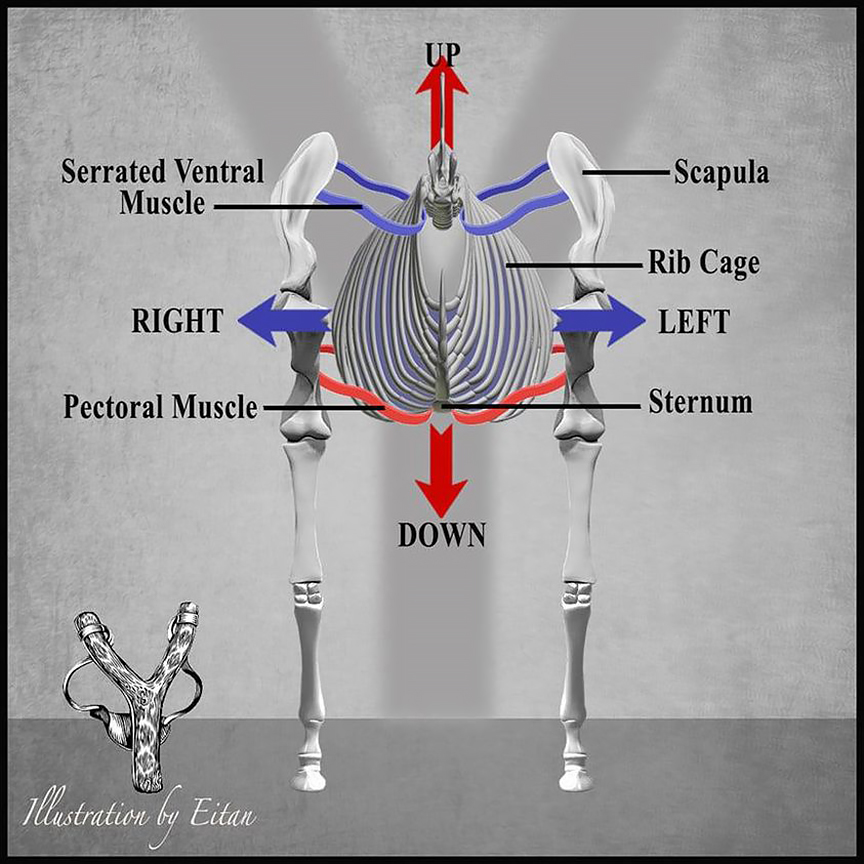

We tend to think crookedness comes from the back and hind legs of the horse. However, it is the horse’s serratus ventralis thoracis muscles and its shoulder blades that also play a role in the crookedness equation. Since a horse is stronger on one side than the other, it allows one shoulder to fall in on a turn or drift out on the other, depending on the stronger or weaker side.

This raising of the frame, if balanced correctly by the rider, will allow those muscles to become stronger and more elastic and aid in the horse learning to hold its own frame.(fig-5)When they connect they raise the withers so they emerge into a higher position between the scapulae and also raise the base of the neck.(fig-6)

This raising of the frame, if balanced correctly by the rider, will allow those muscles to become stronger and more elastic and aid in the horse learning to hold its own frame.(fig-5)

In a young horse, the strength of its sling muscles are often asymmetrical on the left and right sides and that plays a significant role in its crookedness, therefore, we must focus on teaching the horse to use and develop the muscles on its weaker side to make them more symmetrical for balance and self-carriage. In time, the horse will begin to balance in a more upright position without falling in or out of the turns.

The horse’s pectorals muscles get bigger and grow stronger if the chest is balanced up during smaller circles, correct turns and going sideways (lateral work) because these muscles are important for holding the front legs in a vertical position during their stance phase and for crossing the forelimbs during their swing phase.

If the horse is performing the circle well, or a shoulder in or other exercise, the horse will swell underneath you. This is the thoracic sling working. If a horse bulges his shoulder to the outside and jack-knifes his neck to the inside, he is leaning on his thoracic sling (to the outside) and the swell is lost. In other words he finds this more comfortable because he’s just hanging in the hammock of the sling. When the sling is central, the horse cannot help but use it and you will feel the swell. You are now strengthening your horse! You will know that the horse is using himself well. The horse on the forehand is hanging in his sling. All good and correct riding keeps the sling in the middle so that the muscles can lift and engage.

A horse’s shoulders and trunk are heavy; therefore, in training and working toward collection with a horse, a rider must learn how to balance the chest and the trunk upwards so the hind legs can come underneath to provide propulsion and support.

It’s the balance of the trunk that allows the push from the hind legs to go through the horse’s body without pushing it onto the forehand. (fig-7)

Not only the hind legs need development and push. More accurately, the push from the hind legs has to be supported by the upward push of the front legs. So pushing power of the hind legs must be harnessed by the elevation of the forehand so the horse can perform with controlled power in an uphill balance.

(fig-8)

(fig-8)Visualize how the entire forehand of the horse rest in the muscle hammock created by the red and blue rubber bands. The forelimbs are the supporting posts that the rib cage connected to allowing movement up, down and sideways.

The German equine osteopath Dr.Stefan Stammer detailed the importance of the thoracic sling muscles and the tendons of the front legs in developing self-carriage and uphill balance. When the horse uses these muscles to lift the forehand, it is an action similar that of engaging our core muscles. He stressed that the hind legs are responsible for only 20 percent of the lift; the horse’s forehand is the center of motion that dictates the direction of the motion. As a result of these research findings, trainers, riders, and judges can think differently about the concept of engagement as they develop a more accurate understanding of how the horse collects and elevates his forehand. (fig-9)

![]()