Are you Loping, Cantering or Galloping?

The Lope is the western gait!

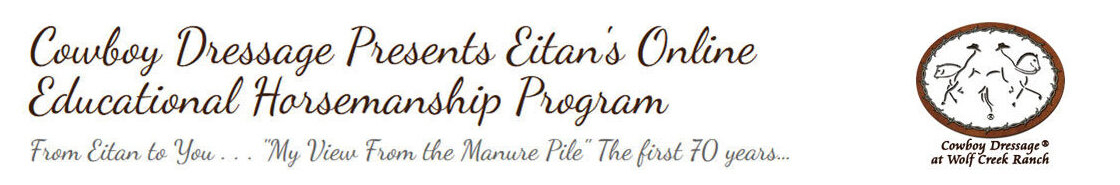

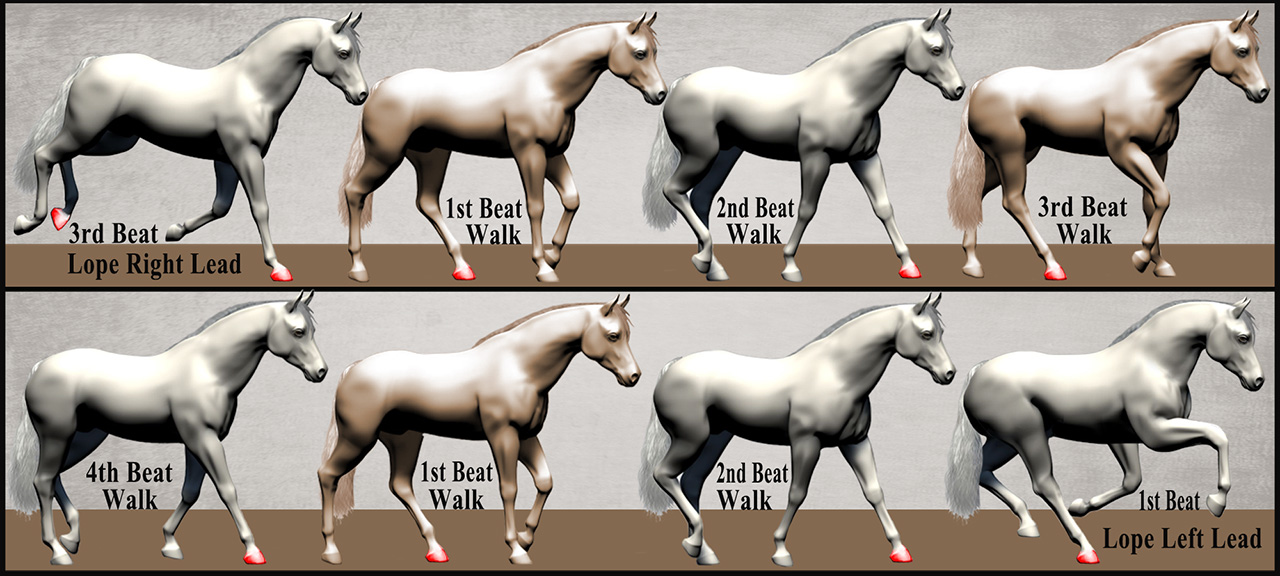

The lope is the three-beat rocking-horse gait for which the Western horse is so widely known.(fig.1.)

It is soft in its cadence and also without suspension. The lope may be either right- or left-“leaded” with the lead of the gait being assigned to the front limb moving without a paired back leg. For instance, the right-lead lope is initiated with the horse’s left hind foot, followed by the diagonal pair of the right hind and left front, and followed by the right front foot (fig. 2).

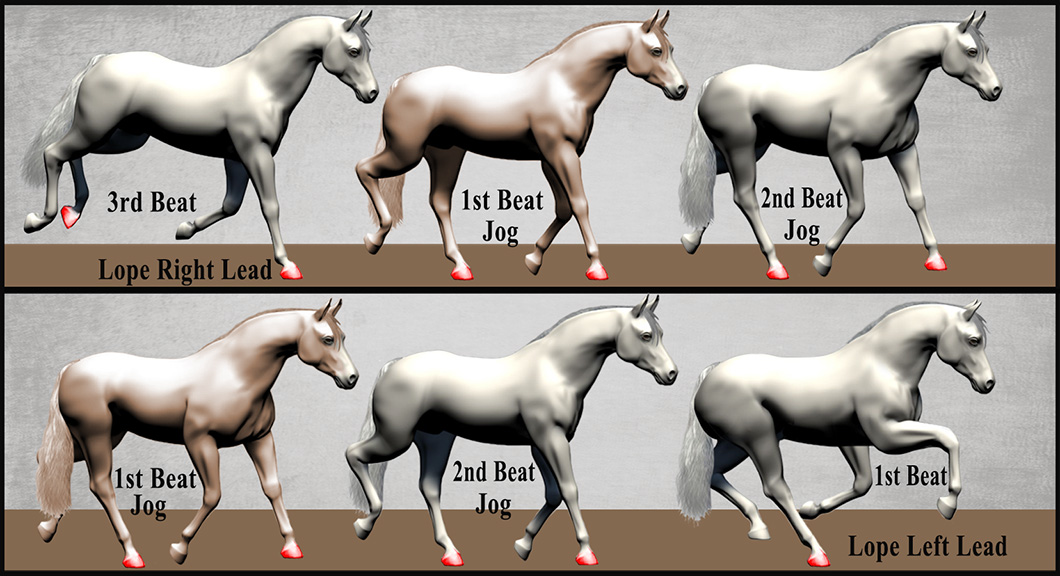

It is often argued that the lope without suspension must be a four-beat gait, but it is the impact of the feet striking the ground that is responsible for the beats of the gate. A true three-beat Western lope has three distinct beats as the diagonal pair is impacting the ground at the same time as a single beat. The suspension phase of the gait that occurs at faster speeds occurs between (3rd to the 1st beat) the leading front foot at the completion of the stride and the initiating hind foot at the beginning of the next stride. In a three- beat lope, the hind foot is striking the ground as the leading front foot is leaving the ground so that there is no suspension in the stride.(fig.3.).

In a three- beat lope, the hind foot is striking the ground as the leading front foot is leaving the ground so that there is no suspension in the stride

The four-beat lope that is often found in an incorrectly moving Western horse is caused by slowing the feet down to the point that the horse splits the diagonal pair of the front and hind limbs moving together. This will appear to create a horse that is trotting in the hind end and loping in the front end. Often called the

“trot-a-lope,” this is an undesirable gait, showing limited propulsion and is not the goal of a Cowboy Dressage lope. Like the walk and the jog, the lope is performed in Cowboy Dressage in two frames: working and free. Also, like the walk and the jog, it is the difference in the length of the stride rather than the speed of the gait that distinguishes the frame of the gait.

Working Lope

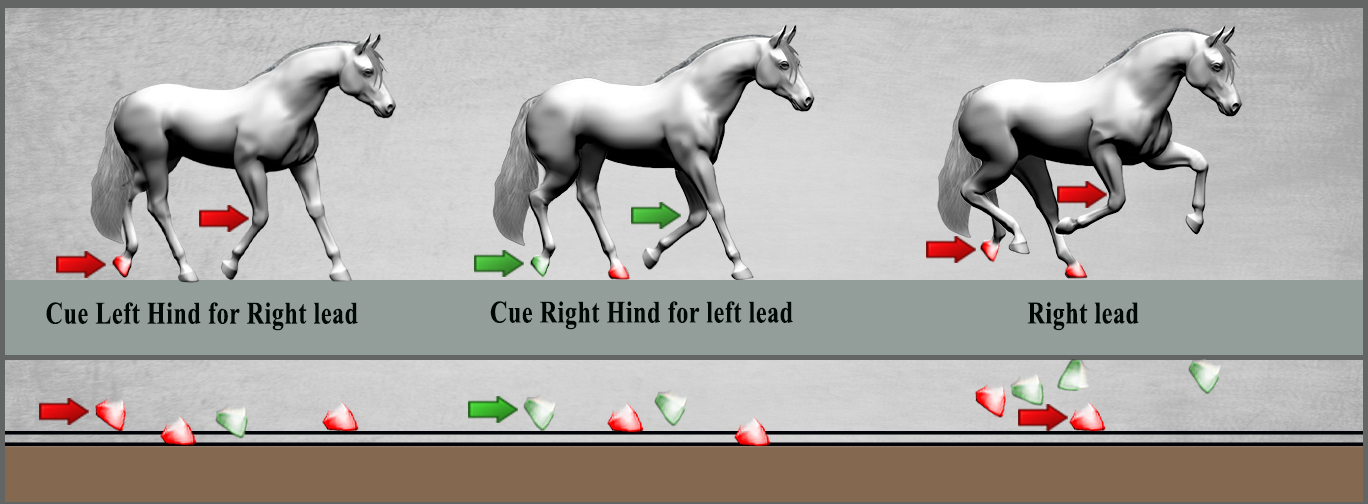

The working lope is a soft three-beat gait executed in a working frame with Soft Feel. The horse should initiate the lope from the hindquarters and step up into the lope in the upward transition without speeding up the working jog or walk into the transition. Again, once the frame has been established in the previous gait, it can be carried upward into the next gait. (fig.5.)

Just as success of the working jog is dependent on success of the balance and softness of the working walk, so too is the working lope dependent on balance and softness of the working jog. Preparing the horse for the upward transition into the working lope from the working jog is accomplished through slight compression of the horse through soft contact, asking him to shift the weight just slightly backward, thus “creating a space” for the horse to step up into. (fig.6.)

young horse is best prepared for the transition through use of bend as this establishes direction for the lead as well as shortens the horse laterally, facilitating the upward transition. You sit up and back through the slight compression with soft contact and use a little inside leg and inside rein to emphasize the bend and direction required in the next gait.

Transitioning Between the Working Jog and the Working Lope

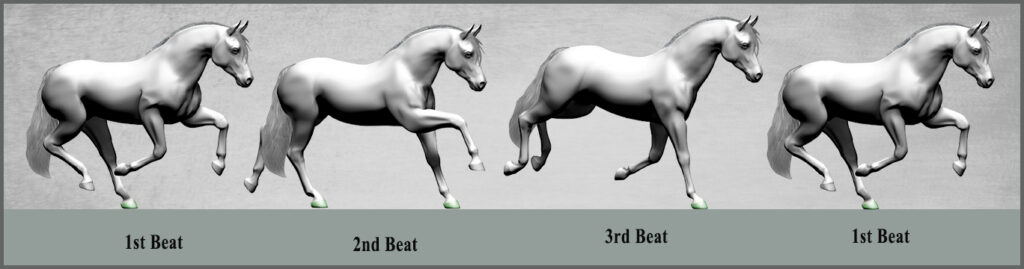

Because the lope stride is initiated by the outside hind leg, the cue must be given as that leg is preparing to move forward. This again is another reason for the rider to be in time with the horse’s feet (fig. 7.).

The cue for lope can only be immediately executed as that hind foot is about to come forward. Because the jog is a two-beat gait moving in diagonal pairs, we know that the outside hind foot is about to move forward in flight as the outside front foot strikes the ground. At that instant, the rider can switch leg aids

from the inside leg holding bend to the outside leg, which cues the upward lope transition. With proper conditioning the horse can learn to “hold” the preparation for the lope transition for several strides, waiting for the rider to cue the transition at precisely the right time.

Once the stride is initiated, hold the working frame, releasing just slightly between strides (fig. 8.).

The lope should be ridden one stride at a time to help maintain balance and frame. Because the working lope is a shorter frame than the free lope, most horses will require the balance and drive from the rider to help them maintain the gait through a circle or maneuver without dropping to the jog or falling out of frame.

(fig.9.).

The downward transition from the lope to the jog or to the walk is more difficult than the downward transition from the jog to the walk. (fig.9.1.)

The lope requires the horse to hold his center of gravity back toward the hindquarters to be executed correctly, but many horses want to fall forward through the downward transition from lope to jog, dropping their balance onto the forehand, causing loss of Soft Feel, loss of propulsion, and making the transition anything but smooth. (fig.10.)

The working lope to working jog transition is made similar to the working jog to lope transition upward. Slight contact with the reins tells the horse to stay in the frame on Soft Feel. Breathing out or dropping your seat bones down and slightly back as the diagonal pair of feet strike the ground allow the horse to step directly into the two-beat diagonal gait of the jog, with- out creating the “jog-o-lope” transition if the gait change occurs when the leading front foot or leading hind foot are cued.

Free Lope

The free lope, like the free jog and the free walk, is a change in frame within the gait that is the result of lengthening and not quickening the stride (fig.12.).

The transition between working lope and free lope, as in the other working

gaits, allows the horse to stretch forward in the head and neck, reaching out and slightly down, thereby stretching the muscles of the topline. As the horse advances from walk to jog to lope, the balance of the gait gets harder to maintain, and rushing and dropping of the weight onto the forehand becomes harder and harder to avoid.

This is exactly why it is essential to school the gaits carefully. You don’t teach a horse to lope by going in endless circles on a loose rein. The gaits are natural to the horse. He understands the mechanics of a gait without instruction. It is the balance of the rider and the elevation needed for the working frame that requires muscles that the horse is not used to using. Teaching the horse

to engage those small muscles and to hold that position in increasingly difficult gaits, transitions, and maneuvers is the very essence of schooling the horse in Cowboy Dressage.

The free lope, therefore, is not asked for in the advancement of the Cowboy Dressage tests until the horse has been adequately schooled through the other gaits and is proficient at maintaining balance and Soft Feel long enough to hold those gaits successfully in self-carriage. Then you can begin to introduce the free frame of the lope to the horse.

From the working lope, lengthen and lower the hands, signaling to the horse that he may lower and extend the head and neck (fig. 13.).

It is important not to tip the horse too far forward onto the forehand. This is accomplished by continuing to ride the hindquarters forward, up under the horse. Soft contact needs to be maintained in the free lope on the lengthened rein, especially to prevent the long reins from flopping and interfering with the balance of the horse within the gait.

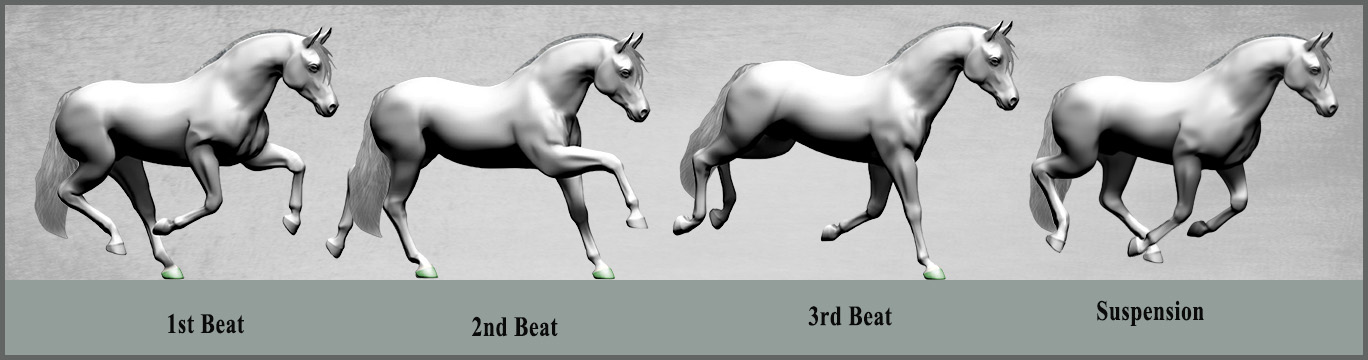

The Canter

The canter is a 4 beat gait with a moment of suspension. The footfall order in canter is left hind, right hind + left fore as the left diagonal, right front, suspension. (fig.14.).

“A truly educated horse must be so secure in the canter that one can set up a metronome to which the cantering horse keeps time, on a straight line as well as in all turns, including the flying changes.

This is not easy, as it requires a high level of artistry on the part of the rider and on the part of the horse’s education, but it is truly beautiful. A horse that is worked and presented this way, will always find the applause of every objective observer, whether they are a connoisseur or a layman. The prerequisite is, and always will be, an absolutely secure posture of the horse, a light but permanent rein contact, a flawless, sensitive, quiet seat of the rider. Oftentimes horses have different rhythms on the right and left lead, e.g. slower strides on the right lead than on the left. One can often see this in competition horses as well who are already shown in upper lever tests. The judges sometimes look the other way, if the horse can fulfill his task more or less otherwise. I consider this fundamentally wrong, because this is the best proof that the horse is poorly trained, as the rider has not gymnasticized one side sufficiently, but he has moved on in the training anyway without correcting this absolutely fundamental mistake first. Overlooking or ignoring a false foundation always takes its toll later on, because the horse will never go in correct collection without showing some kind of unevenness. Therefore: Ride a horse like that forward again first, and make it evenly permeable, until the canter is equally engaged on both leads and can be ridden effortlessly in the same rhythm. Only then is it permitted to try and shorten the canter strides.”

(Oskar M.Stensbeck, 1931)

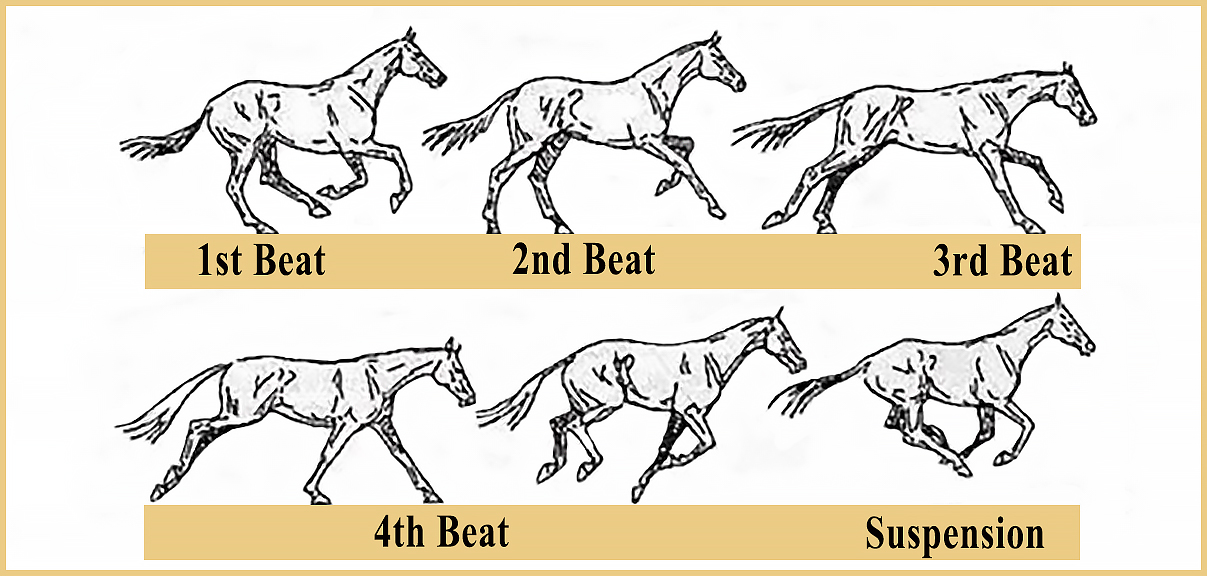

The Gallop

The gallop is the fastest gait. This is the gait you see race horses performing when they’re running down the track. The gallop is a four-beat gait and the footfall sequence is as follows: a hind foot, followed by the other hind foot, then the front foot on the same side as the first hind foot that stepped down, then the other front foot (fig.15.).

That’s considered one stride, and then the pattern repeats just like with the other gaits. It’s rare for the average person to ever ride at a true gallop… most horses and riders, even if they are going really fast, are actually only doing a very fast canter. The horse’s feet still maintain a three-beat pattern so it’s still technically considered a canter. Only when the feet change to four beats can it be considered a gallop. It’s very rarely will an average horse cross over into a true four-beat gallop. (fig.15.16.).

Diagonal Advanced Placement or DAP.

There is a well documented phenomenon commonly spoken about in the dressage discipline called Diagonal advanced placement, or DAP, can be found at the trot and the canter. The USDF’s Glossary of Judging Terms defines it as being when the “hooves of a diagonal pair of limbs (in trot or canter) do not contact the ground at the same moment.”The trot has always been thought of as a two beat gait, and the canter as a three beat gait with the diagonal pairs of legs landing and taking off together. However, closer analysis using photography and stop action video has shown that the diagonal pairs do not always land together, resulting in what is referred to as dissociation or DAP. When the hind leg of the diagonal pair touches down before the diagonal foreleg, it is known as positive dissociation or positive DAP. When the foreleg of the diagonal pair touches down before the diagonal hind leg, it is known as negative dissociation or negative DAP.

HAPPY TRAIL!

![]()